Alaska, July 2016 – A Big Moment For DYP

What is the key to having an edge in my genre of photograph in 2016? It cannot purely be technical camera fluency as that would enfranchise photographers across the globe – many of whom doubtless know their camera guide appendix far better than me. Nikon may have made me an ambassador, but not the basis of my understanding of page 239 of the manual. Of course an innate sense of compositional balance and unerring focusing ability helps, as does a literacy in the language of light. But again, whilst this may narrow down the field, none of these skills are uncommon. I am always conscious of the fact that in 2016, everyone is a photographer.

My firm contention is that the key to taking transcending photographs in the field, is access to great content and this comes from research, perseverance, occasional bouts of bravery and most of all logistical excellence. These variables collectively morph into one goal – “precision”.

Without an obsession with precision, the game is down to luck and luck is – by definition – a leveler. I take issue with those that say, wildlife photography is about luck, because as I grow older (and looking in the mirror I see that have aged a great deal camping in Alaska over the last 10 days), I can reasonably argue that research and logistical excellence tilt the odds in the favor of the applicants.

I want to be the best – why settle for anything less in this trade? This is not ego talking, it is natural to be the best you can be. To succeed it will not be about me learning about new function on the camera, it will be through a constancy in my commitment to homework.

Alaska is the perfect example of this dynamic. To go on photographic assignment there is much more a test of map work, spontaneity, people skills and quick thinking than it is of photographic prowess per se. To do a good job up in this remarkable wilderness requires a respect for logistics – indeed that is what a lead photographer in the true wild must be – a logistics expert.

Let’s start with a simple check. Google ”Best places to photography grizzly bears in Alaska” and there will be about 30 options articulated. The favorite places are designed for “weekend warrior “cameramen. Brooks Falls in Katmai for instance is effectively a zoo – with heavy park warden presence and soulless viewing stands. There is no joy for me in a place like this – and I did pop in to seek that confirmation this week. I am better than sitting on a stand with a long lens along with 40 amateurs.

Kodiak Island has a huge number of bears, but because big game hunting is legal there, the bears are skittish and sometimes dangerous. Hallo Bay – site of the Disney Film “Bears” has taken success to their heads and the bear viewing is overrated, expensive and too accessible. They also regulate far too heavily – I know – I spent 2 days there last week being told where to sit. That is like asking Liam Gallagher not to swear. Most of Google’s 30 favorite places, hold no visceral grip on me – they are mainstream and dull. I don’t need to be told to stay 50 feet from a bear, when I have been 2 feet from a polar bear.

I like to be close, not be policed my 20 years olds on a summer secondment and I like to be on my own if possible. Setting up sensible practical remote control positions leans me towards remote river banks and the summer salmon runs. Each river has its own unique salmon run and the times not only vary between rivers over a 12-week period, but each river has a different pattern each year. If the salmon run on a specific river starts on July 22nd one year, they could run 7 – 10 days either side of it the next year. This requires a need to be spontaneous and be on the ground picking up grass routes detail. “How are the fish running?” became my opening gambit the second half of July. I am no fisherman either.

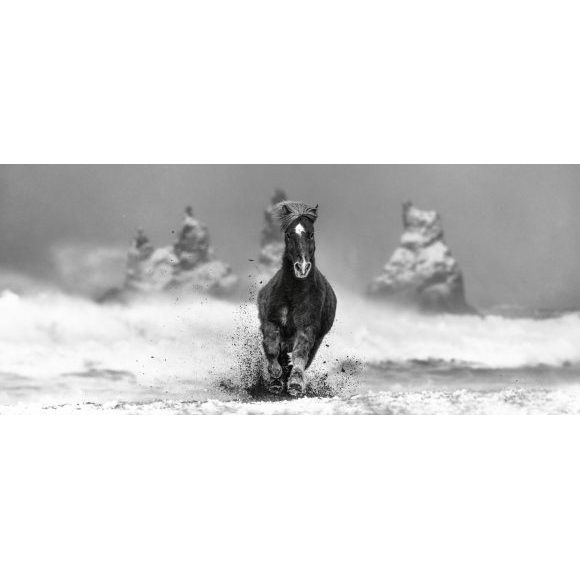

Over these last 10 days, I have had one picture in mind – a wide angle remote control shot of a big bear on a river’s edge. Something immersive and very close. But the 2016 season has not been predictable – berries have been plentiful and bears love berries as much as salmon, so traffic in some rivers has been abnormally light.

But bush plane by bush plane. I narrowed down my focus to an area I knew well – 70 miles south of Illiamut on the Alaskan Peninsula. We deliberately flew very low over Funnel Creek earlier this week and saw at least 6 very big bears fishing up river and so we touched down in the tiny village of Illiamut to discuss logistics. Every village in Alaska has a landing strip.

The next day, we were dropped off by float plane on a tiny lake to walk the 4 miles through tundra and the river itself to the precise area we saw the bears. It is not for the faint hearted as these are big bears and it is the true wild.

The location was even better than we dared hope – in 6 hours we saw at least 15 bears. I knew these bears were not necessarily dangerous, unless you do something really stupid or are incredibly unlucky on your positioning between sow and cubs. I have studied bears for 4 years now and I am not intimidated during the salmon run – they are far too busy fishing to worry about a human, let alone maul a human.

There is no mileage photographing a bear with a long lens – just like a lion, it has been done before – it is hackneyed pulp. What I wanted was a bear 3 feet from my ground up camera. Not easy – as why should the bear walk towards a camera, never mind look at it – cameras don’t smell?

The chance came yesterday half way through the day and we waited over an hour with the camera just 20 feet from the bear. I have made my reputation partly through the use of remotes and it is a language I am now fluent in – manual pre selected point focus, lens, aperture, distance etc. I know what I am doing here – largely from hard lessons learnt in the past. By getting it wrong, I now know how to get it right.

It all happened in 5 seconds. I thought I had missed him to the right, but all was okay.