“Fire and Fury?” – 8 Days in North Korea

In early August, I spent eight days in North Korea. Given the escalation of tension between the reclusive country and America, my timing for this long arranged trip was luckily about as good as it could be. It was one of the more demanding assignments of my career, simply because the fine balance between the need for personal safety and the need for content is not defined in the same way as it has been for me in other countries.

Many of the rural locations that I visited were unequivocally virginal territory for Western photographers. With a travel ban to North Korea now in place for Americans, I felt a responsibility to do a good and accurate job. The access was secured after months of negotiation with the North Korean Embassy in London – I was invited into the country as a guest of the Party.

I believe that the three most important words for an assignment photographer coincidentally all begin with the letter R. Research is vital and then there is also a need to be relentless. The third R is the toughest – relevance. Whilst I spend a great deal of my time photographing endangered wildlife, I think it is a little lame to say that all pictures of elephants or lions are relevant because the imagery raises awareness of the beauty of these animals and in turn our poor custody of the planet.

For sure, great bodies of work in the wildlife genre can hammer home an important conservation message, but it is a stretch to say that such work is “top tier” relevant. North Korea struck me as being both extremely relevant and very hard to access.

Good access is often the key to ground-breaking original content and access to most places can normally only be secured through persistence and resourcefulness. I knew that if I got in, I could probably deliver with content. The challenge to get into the country is insurmountable for most but I felt I had a better set of cards to get in on my terms than others. I did the same with South Sudan a couple of years back and more recently in Makoko, Nigeria.

I also sensed that North Korea would not be dangerous for me – in the way that say Syria, Mali or Somalia could be. I have two children and I only take very measured risks. This was a measured risk.

Friday night down the pub in the capital

Friday night down the pub in the capital

Americans are much more concerned about safety issues in North Korea than Europeans – and maybe rightly so. Many American friends of mine pleaded for me not to go and whilst it was flattering that they were worried for my safety, I think they overplay the dangers.

The idea of the trip came from a senior executive producer at NBC. Russian by birth, she was originally interested in the idea of me photographing Putin. But when I went to see her in Washington, she mentioned that she also had a political contact in London that could help with a formal invitation from the DPRK. This excited me as already North Korea was becoming very topical. As weeks went by, the Putin idea lost momentum because of the Trump election dynamic. She made the introduction to the politician who then introduced me to the North Korean

Ambassador to London. Four months of negotiation and I received a formal invite in July. I would be assigned to a senior minister who handles many EU trade relationships.

My goal was – as always – to have original content. North Korea is the most secretive, isolated and paranoid country in the world. Cameras in the hands of foreigners are a clear and obvious threat to the Party’s sense of privacy and their internal propaganda. They will deal with unauthorised possession of cameras in a number of ways and none of them are good.

There are two ways to enter into North Korea – overland from China or – more usually – by plane from Beijing. Taking the overland route – by train – is a long and very high risk strategy. Those lucky enough to

have been granted a visa will have their luggage checked for decent cameras at the border. This is a full on check – not a cursory or casual one. Anything suspicious and they will either have their goods taken, destroyed or they will be sent out of the country.

If a cameraman manages to circumvent security and get off the train anywhere inside North Korea, but before Pyongyang, and start to take images, they have two issues – the logistics of getting around with the spartan infrastructure and secondly the risk of being caught. There is the chance that means jail. We all now know what happens from there. That is not a measured risk at all. You cannot travel independently in the hinterland of North Korea – the roads are empty and public transport is very limited.

"I never saw another camera in my time outside the capital"

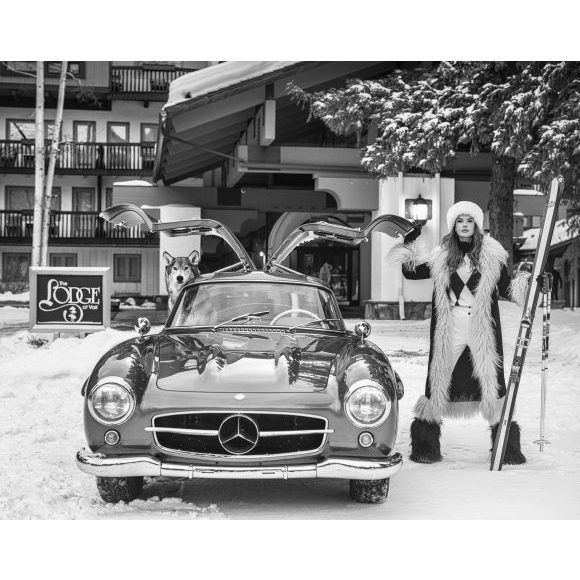

Access to the biggest steel plant in the country

Access to the biggest steel plant in the country

Westerners arriving by plane at Pyongyang airport face the most comprehensive baggage check of their adulthood. Phones are switched on and looked through, DVDs played, books read. I was being met by Ministry officials and customs were expecting me, but nonetheless, my cameras were thrown around as if they were plastic toys.

No good cameras are allowed through the airport, unless the possessor has someone senior the other side vouching for him. Even if a rogue photographer – working alone – somehow manages to get a good camera through the airport, how are they going to use it out and about in Pyongyang without detection? The military presence is formidable and they have a big issue with cameras.

So working in North Korea as an “uninvited” overseas photographer is virtually impossible and extremely dangerous. Being invited in – as I was – is the only option. But it is a long and expensive process.

I think I was in fresh territory for photographers after three hours drive from Pyongyang. I never saw another camera in my time outside the capital.

Beach party in Wonsong

Beach party in Wonsong

I know that there were over 100 international press present for the big military parade in Pyongyang in April. North Korea always wants international coverage for this show of its military power. But this was a massive staged event and offered no insight into daily life outside the capital. It is a ceremony – albeit a rather disconcerting one. No camera crew or photographers would have left the capital other than to get to the airport in the suburbs. There are check-points on all roads in and out of Pyongyang.

The pivotal issue on this trip was to make sure that I did not become a puppet for their propaganda. The locations were chosen for a reason and I had to work my way around this riddle.

The senior official that greeted me at the airport would lose his job at best, if he were seen to have shown me content that would further damage the image of the DPRK. The government had arranged an intense itinerary of visits to factories, educational facilities, leisure facilities and theatres that would show the country in its best light – in fact a total of 30 scheduled stops. All were manifestly destinations of which the Party are proud.

I knew that I would have to work around this and over time gain their trust. Opportunities would then emerge to “steal” imagery, rather than being offered it on a plate. Apart from places of heavy industry, I had no real artistic interest in the destinations they took me to. However, getting to these work shops or elite sports schools served a purpose in itself, as we had to travel deep into the north east of the country to get to some of them.

I had always requested that we travel into rural North Korea. Intuitively, it seemed that the longer we had on the road, the more opportunities would become available. Furthermore, the greater the distance from the capital, the more likely I would be to enter towns and villages that had never before been photographed by a western photographer.

At the heart of my approach was a sense that there was a potential arbitrage between what they thought was normal and what others would find to be highly visually arresting. The lively beach resorts of the east coast being a case in point.

Trust was everything. I had to emotionally invest in the men assigned to me. North Koreans have a drinking culture and the first thing I did was give them some bottles of Scotch Whisky that I had brought in. I also didn’t take my camera out for the first 12 hours in the country. I asked permission every time to take a picture and I worked my way gently in so that they became more comfortable with me. From the outset, I could see that they were nervous – more nervous than me.

In total we travelled more than 800 km often through stunning countryside. At all times, I had my camera ready to steal whatever came my way. They became relaxed about this, simply because they could not be blamed for whatever greeted us on the road. We would never have gone near a military sensitive area – for all our sakes.

It was still a process of constant negotiation and being told “no” a great deal. But the more “no’s”, the more chance of the occasional “yes”. They wanted me to be happy with their service, but equally they certainly didn’t want to get any rebuke from the powers above. The latter was always going to hold sway and this made the assignment a challenge. But I think I did all I could and maybe a little more.

The constant warmth and friendly nature of the locals surprised me

The constant warmth and friendly nature of the locals surprised me

The further from Pyongyang that we travelled, the more welcoming the locals became. they offered me drinks, food and games of table tennis. The culture of North Korean people is peaceful and conformist. It helped of course that I was with their fellow countrymen, but even when I strayed, the welcome was there. By the way, they are outstanding at table tennis – as I learnt to my cost.

The people of North Korea are fine with having their picture taken. But not so the military – these have to be “stolen” images.

Aggressors of North Korea – and there are many – can only really be enemies of the Party, not the millions of people that abide with the Party. Outside the military, North Koreans are peaceful people. It is a culture of music, dance and harmony – not war. They also like a drink – there are pubs in Pyongyang that put London to shame in terms of beer drinking. They are not individualistic people – rather they are what Italians call – Communitirists. I am not sure whether that is a word, but it serves its purpose.

Sadly, the economy appears to be a total basket case. The vast majority of the 25 million people are without regular electricity or drinkable water. I would suggest that the country is at a similar level to post WW II industrial Britain. As I travelled around the country I saw many people doing the most menial of jobs such as weeding road verges or sweeping dirt from one spot to another. There is a sense of a time warp – the economy simply has not evolved.

I don’t see the nuclear threat the way some Americans do – or their

President. It is a game of chess and nuclear capability is North Korea’s Queen. I am clearly not as informed as the CIA, but what I do now know is that Kim Jong-un is there to stay – as that is what his people want. As a leader, he is worshipped at a level I have never seen anywhere in my life – it’s almost like ‘Beetle-mania’. There is no ‘Arab spring’ style revolution. The nuclear programme has always been a deterrent, not a declaration of intent.

The supreme leader’s removal will only come from America by force – not the Chinese and certainly not the Russians. Domestic economic reform is very necessary and there is a school of thought that when the nuclear deterrent programme is complete, more money will be channelled away from the military – which must be a huge fiscal burden currently. Economic improvement will only strengthen his popularity.

The Party and the people just want to be left alone – for better or for worse. I rather sympathise with this. They crave the right to be who they are. It is a very proud country.

As with most troubled countries, North Korea is not a simple situation. The economy is worse than I imagined it to be, but the acceptance of the quality of daily life is higher. I saw as much happiness and laughter in the eastern cities – as I see in the streets of New York or London, perhaps more. There are less raised voices and there is more conformity for sure. North Koreans are like ants – they do what is done – and the regime ensures they know no better. I kept on thinking of the film – The Truman Show.

And in the meantime they adore and respect their Supreme Leader – Kim Jong-un. I was left in no doubt about that and an analysis of whether this adoration is contrived rather than merited was not the premise of this assignment. I just wanted to see what really goes on “in the void”.

Equally, I left preoccupied with the irony that there can be no greater contrast than the respective domestic popularity of the leaders of the US and North Korea: One is mocked for his autocratic style and juvenile behaviour and the other is the 35 year old leader of North Korea.

David interviewed about his North Korea trip on Fox News

David interviewed about his North Korea trip on Fox News