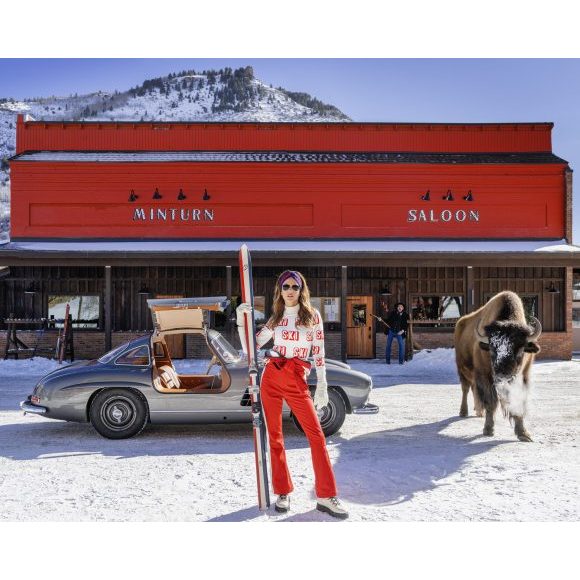

ANTZ

Chittagong, Bangladesh 2015

The ship breaking yards of Chittagong, Bangladesh offer a mystical allure that is incongruous. There may be romance in the art of building big ships – my family background in fact – but there is little for the romanticist in the primitive dismantling of these vast cathedrals in the sky on these muddy shores to the north of the country’s second city. This is a nasty, dark and soulless place – ostensibly it offers nothing but an elemental canvas on which to frame extremes.

However, the haunting rawness of the factory beaches is spectacular – there is so much more for artists to feast on here than at the beaches of Saint-Tropez. This is emphatically life on the edge of our planet and its depiction offers a good opportunity to propose that beautiful art is not exclusive to the portrayal of aesthetically beautiful things. That linear a relationship would make all our lives one dimensional and uninteresting. Very few western photographers make the trip to this part of the world and the corollary of this is the chance to engage and maybe even shock with the results of the assignment.

Also, the window in which photographers can paint onto this canvas is rapidly closing and therein lies the reason that I was anxious to travel down to Chittagong in 2015.The yards are being tidied up, with less child labour, better safety standards and a greater degree of worker rights. What was hell is still hell, but as each year goes by, the ship breaking yards are adopting more humane practices. There is now organisation to the chaos.

Furthermore, access for all visitors to the yards is now strictly prohibited and even workers are not allowed to take their phones to work for fear of new footage from the camera application further embarrassing either the government or the private yards. Photographers are not welcome here and any English speaking fixer will tell you this immediately on arrival. This is a massively important industry for Bangladesh – each boat brings in $7m of revenue, which then multiplies as it moves down the food chain.

The road inland from the yards has heavy security and my preconception that bribery at the gates could work was misplaced. The beaches that Edward Burtinsky cleverly portrayed with his trademark dispassion some 12 years ago, are strictly out of bounds from land. The only alternative was to land ashore quietly by fishing boat and then approach the factories by foot.

This is a dangerous route that few photographers, according to Maajhi my appointed fisherman, have chosen. The tides are fast, the beaches are sinking mud, not sand and the workers on top of the vast tankers 500 feet above the sea will throw pipes and debris at you, if you invade their space. It is as hostile as it can get without the use of guns.

So that was exactly what we did. I had two goals on this assignment and one wish. The first goal was to offer a sense of scale, the second was to capture a sense of this industrial place and then my wish was for the cloud cover to be stormy. It seemed that this was a place where ‘angels fear to tread’ and therefore a sky that suggested impending trouble was more apposite than ‘picture postcard’ blue. (It is always so).

The picture below – which we have called ‘The life of Pi’ emphatically scores on the sense of scale. The young fishermen offer context and they help tell a story. The light worked well and there is a pleasing composition particularly with the eye being led into the central vortex framed by the hulls. There is a great deal of information in this picture and as with ‘Mankind’ it can hold the attention for a long time. It is a strong image.

Yet, as I looked at the image again and again in my modest hotel bedroom that night, I knew I wanted more. The weather was too good that day for a start, but far more importantly the tide was in and that was manifestly a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it was a positive as Maajhi and I could use the high tide to get very close to these enormous structures that – panel by panel – were being dismantled. But the tide prevented a real sense of place – no workers on the mud, no metallic scrap yard chaos and no juxtaposition of project management of ‘Noah’s Ark scale’ occurring on a muddy beach in 2015.

The next day, I was singularly focused on these issues and left my room at 4.30am to be with Maajhi before dawn: This allowed us to reach a particularly apocalyptical part of the yard I had noticed earlier in the week, before the tide came in. Encouragingly, the weather was hot, but clearly stormy.

The security detail was light – it was too early for anyone to worry about photographers landing by sea, but the mud was horrendous and very unnerving. I had some fairly precious equipment in my hands as I staggered vulnerably through the mud.

The result is a big moment. I remember singing ‘Matchstalk Men and Matchstalk Cats and Dogs’ as a kid and as an adult I have great affection for AS Lowrys industrial work. Maybe it comes right back to my family roots – shipyards, scale and hard work.

This image ‘Antz’ has not just a poetic evocation of size and scale, the onshore detail of workers coalesces with the mighty tanker to offer that true sense of place which I was looking to capture. The gathering storm – it rained heavily half an hour later – was fortunate detail as was the accompanying early morning shaft of light.

But it is the worker detail that lifts this photographic essay – the seemingly senior figure at the back enjoying an early morning smoke as the matchstick 3 walk towards him.

I feel confident in my assertion that a Nikon SLR has never been in the spot before and I doubt any photographic practitioner will be mad enough to try and shoot from the same angle. There is simply too much to organise and – of course – as of now, it has been done before. Besides, the ship will soon vanish. ‘Antz’ is a true moment in time.