Letter From Borneo

We will leave to the Falkland Islands from Santiago, Chile this Saturday before sailing to South Georgia, secure in the knowledge that this has now been an outstanding year for both new content, print sales and contributions to conservation NGOs and other charities. Who knows what we will return with from our two-week trip to a wild destination at the bottom of the world, but there has never been greater momentum in what we are trying to do. It is an exciting time for DYP and I am extremely fortunate to work with good staff, strong brands and hardworking business partners across the world. This adventure may have started with me, but I am now joined on the journey by so many talented people.

At our core, we are an “original content” brand and we have no game if we fail to deliver on this simple objective. But if we can do this, all other goals are achievable with work ethic and the right network of supporters. In 2018, we look set to raise over £2m for charitable causes. This is far in excess of our target at the start of the year and I thank all those that have made this possible with their generosity.

I have a high degree of conviction in my view that artists, like golfers, financial market traders and London buses have streaks. There can be quiet periods and then, for whatever reason, a winning run is put together. This is exactly what has happened to us since early September and we are all delighted. The retrospective analysis of “why” is always hard, because ostensibly it should be a random walk - recording nature is certainly a crap shoot most of the time.

When I worked in finance, my bible was Nassim Taleb’s seminal work - “Fooled by Randomness”. The central premise of the book is that we tend to attribute good things that happen to our own good judgement and the bad things that happen to bad luck, whereas the truth almost always lies somewhere in between.

I do think that confidence can help in putting a run together as there is a circularity that spins around to influence our own decision making. This is true in sport, the poker table and also in photography. Original content by definition demands an avoidance of the road well-travelled and this is an easier path when there is a spring in your step.

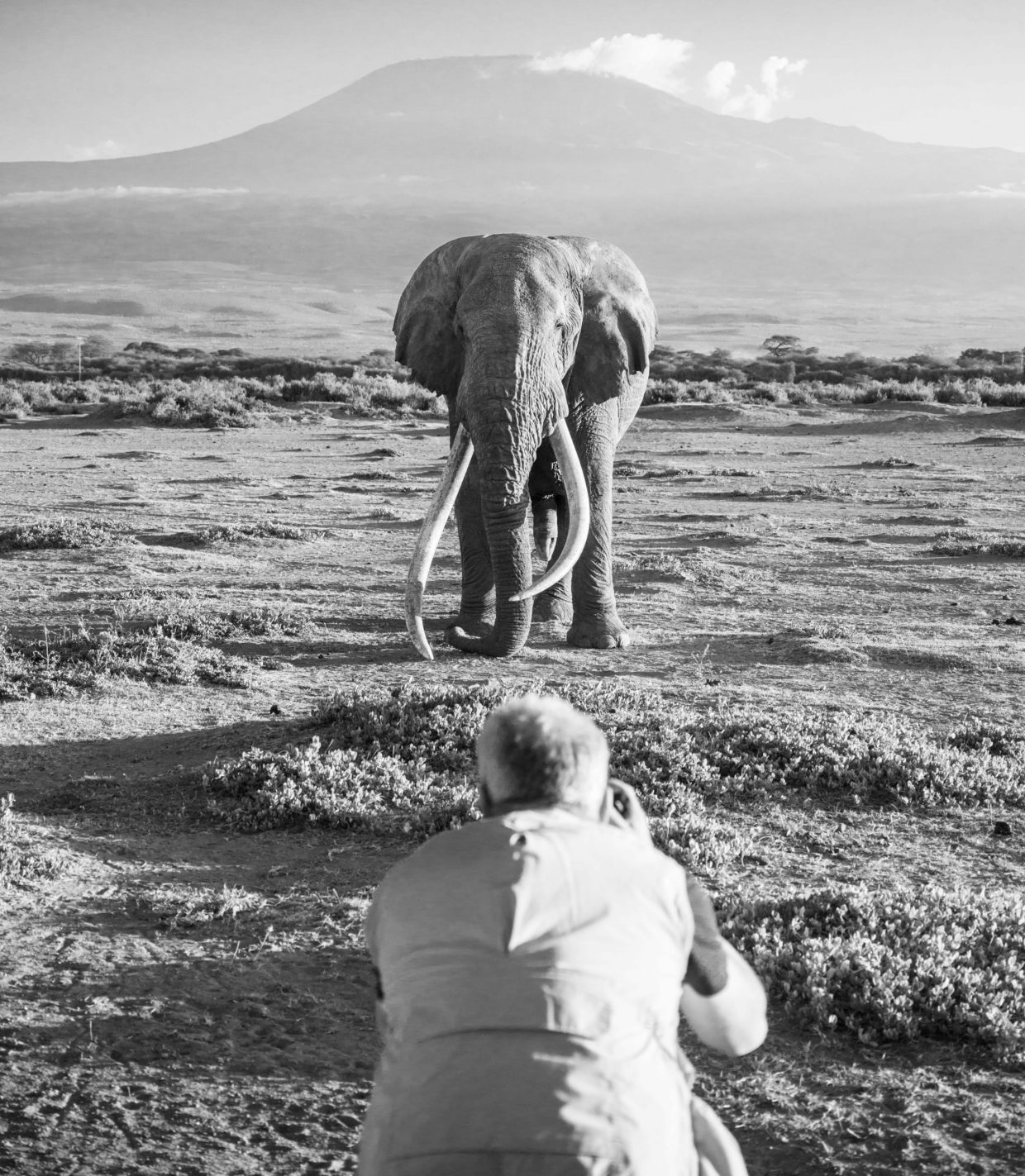

I took one of the most important pictures of my career this autumn - Africa. I will leave others to decide where it ranks in my portfolio. It has certainly received unprecedented levels of comment and interest and is already difficult to buy.

Some have suggested it could be an iconic image - but that is something that an artist cannot himself determine or comment on. I even slightly flinch when others use the word. All I know is that I become emotional every time I see a big print of Africa and, I am not sure there is anything I would do to improve it. That is an extremely rare analysis from me - normally there is something, however small, to be changed.

I said to my team the night after I took the photograph that it could be our first £1m image and this has been proved right. That kind of return from one image has been 35 years in the making - it has not happened overnight.

I know it was a lucky image, but I also believe the amount of time we have invested in Amboseli over the years, and the infrastructure of helpers we have put in place, narrows the odds in our favour. The position I took up on the ground near Tim the elephant was not that of someone who has an embryonic relationship with the ecosystem, Tim or most importantly of all, the Kenyan Wildlife Service rangers.

Our most recent assignment to Borneo provided another case study not only in terms of what we are trying to do, but how perhaps winning streaks can be maintained by having the confidence to roll the dice and take a chance with the right degree of time and investment.

Orangutans are not hard to find in Tanjung Puting National Park. Fly from Jakarta to Pangkalanbun and then charter a rickety house boat that crawls up the river towards Camp Leaky. You don’t need to be a friend of Jane Goodall or Hilary Clinton to find the Orangutans. The list of celebrities that have taken this journey is long - it’s rather like the photos on the wall in an Italian restaurant showing the owner with every famous actor, footballer or politician that has ever eaten there. These orange people have become emblematic of the fight to save our planet and the tourist footprint through this jungle has risen.

The orangutans are essentially wild, but there are feeding platforms that at the same time daily are covered with freshly picked bananas. Human interaction is part of their daily routine - much like the gorillas in Rwanda. The presence of the orangutan is almost guaranteed and with it the presence of many visitors - some of whom seemingly carry every single piece of camera equipment ever invented. It costs $1400 a day to see the gorillas in Virunga, but it costs nothing to see the orangutans in Borneo. As a result, this is the preferred primate adventure for many.

But for us this can be a miserable experience and totally at odds with what we are trying to do. The term “original content” is a misnomer if there are 15 other photographers firing away from the same viewing stand. It is entirely possible to turn up in the jungle at feeding time and feel a complete fraud. I closed my eyes at one stage and listened to the camera motor drives firing off from everywhere. I imagined that I could have been behind the 17th green at the recent Ryder Cup - except, of course, not many of the matches reached that far.

For most of us, Borneo is a long way to go to be such a soulless experience. The reason that this is the preferred option for almost everyone is that sightings are guaranteed and so it plays into the risk profile of most visitors. To travel to this jungle from Europe is at least six flights round trip and a good amount of money and from America the number is even bigger. Imagine the stigma of returning home from the jungle and not having an orangutan picture to show to your work buddies. That would be highly embarrassing and that’s why Camp Leakey and the other camps downstream from here are a known known.

When Scott reached the South Pole only to discover that Roald Amundsen and his Norwegian crew had beaten him to it, he was, by all accounts, devastated and the rest is history. On a laughably more modest level, if we reach our final destination and there is a bigger crowd gathered around the subject than there would be watching a second division football match in Scotland, I lose any appetite for the day ahead. My mood turns dark and full of self-loathing. The one thing that unites all my strong images - bar none - from this year, is that there was no other photographer within five miles from where I was filming.

On this occasion in Borneo, I took my 15-year-old son along and time on the tourist river gave him the opportunity to photograph the orangutan. He was so excited to see a big male, but he also knew me well enough to know I was emotionally disengaged from the process. Equally he also knew that I had a plan to push some boundaries as the trip unfolded.

I find the jungle a tough place to work. Give me the cold of the arctic any day - whether it be minus 30 degrees or worse and give me also the heat of parts of India or the deserts of South West America. In both cases there are remedies. We do not sleep in igloos in the arctic and we do not need to be outside at midday in the heat - wherever we are - as the sun is too high to shoot.

But the jungle offers no refuge or respite. It is energy sapping, uncomfortable and full of little insects that won’t rest until they have bitten you into submission. There is the water to bathe in and cool down, but this is a communal facility, shared with snakes and crocodiles, which, at the margin, somewhat lessens the appeal. Nothing is safe in the jungle and I can only imagine what it must have been like to fight a war in these locations - whether it was Burma or Vietnam.

"...this could turn into a fairly vanilla trip unless we took a risk and invested some time and money on plan B."

From 5 pm on the second night, as darkness started to fall on the river and tourist boat after tourist boat passed by with celebratory waving hands, I started to form a plan with my guide - the very best guide that one can find in these parts. I felt that after some of our recent successes, this could turn into a fairly vanilla trip unless we took a risk and invested some time and some money on Plan B. If Plan B did not work, we had had a good month and that’s the way it goes. In other words, I was in the mood to gamble.

I knew that we had access to somewhere extremely remote and entirely different than the boat park where our river boat was initially moored - it just meant a very long trip from where we were. We would be entering the open ocean for a stage and our guide was worried about the moon cycle and the chance of some very big waves. Tragically Indonesians know more than most about big waves and high tides and his word was necessarily sovereign. To get to where he wanted to go, we would need to start our motor boat journey at night to avoid the tides.

After a restless night, we left in two tiny motor boats at 4 am. Sometime later we were in the open Java Sea heading far from the madding crowd. By 7 am we landed at a remote orangutan research base and our guides received instructions for the next leg of our adventure. I cannot sadly mention names or places for obvious reasons - as I would like to go back and when I do, I want to be on my own.

As we travelled deeper into the jungle and the river narrowed to little more than twice the width of our tiny boats, I felt an inner peace from the knowledge that we were doing exactly what we should be doing. I said to my team that even if we did not see an orangutan, the scenery was quite breathtaking and our drones would capture the essence of the road less travelled.

This is what DYP is all about, not sitting in a jungle grandstand with 30 other photographers. Even if there were no orangutans - we would come every day until there were. After all it was only an 8-hour round trip.

The final stretch of the journey brought a harrowing first hand exposure to the destruction of rainforest at the hands of the palm oil industry. Mile after mile of dead or charred trees hugged the water’s edge - it was visually unique scenery for me - the greens of plants and burnt blacks mirrored with crystal clear reflection on glass like water.

I have been to many places in my life that are “other worldly” in their colouring - the Atacama Desert, Death Valley and the Namib Desert for a start, but they have been like this since the planet as we know it was created. But here in the jungle of Borneo, was a place that had been made other worldly by humans of my generation. That was the shocking discovery that early Sunday in October. Three days later, America celebrated Halloween - but here was our very own fright night.

What unfolded an hour later in the jungle was a most spoiling and memorable experience. It was everything that we hoped for and a little more. The location allowed for immersive and powerful film making.

The two images that we print in colour in the report are as good as I have ever done with any primate, but far more importantly they tell a story that needs to be told. When we left the charred area of woodland, I said to my team, let’s pack up, find a hotel in the nearby town, have a shower and get some sleep. Our job here was done. There was no way we could expect to top this and we were all shattered, sunburnt and bitten. That was one hell of an enjoyable bath that night.

So the momentum we may have had recently in garnering new material could well be down to luck, but we are also becoming more aggressive in our perception of what is not good enough and more prepared to reinvest to push boundaries in our locations and in our financial partnerships. Tough editing and strong reinvestment is a function of confidence. This assignment would not have been successful were it not for our guide and his spotters in a most remote part of the Tanjung Puting National Park and we have improved the way we work with key ground support. They need to be treated as partners.

I have great respect for Indonesians - they have had to put up with such terrible tragedy in 2018 and even before then, life for many of the population was not easy. Yet they are - in the main - honourable, hospitable and always seem to be smiling or at least half smiling. That put them one up on me, because whilst I hope that I am honourable and try to be hospitable, I can be grumpy a great deal of the time in the field. I guess it goes with the territory.