Letter From Iliamna, Alaska

If this fairly shoddy iPhone picture above was shown to 100 students at an American College and they were asked to identify the state in which it was taken, I fancy that almost all would answer correctly with Alaska. But what is the clear giveaway? It can’t be the American flag because whilst Alaska’s military personnel (as a percentage of the population) is one of the highest in America and whilst some locals may still be hung up on their Russian heritage, many other US states are as fiercely patriotic as Alaskans. Nor would it be the moose antlers, because whilst they may rule out the southern states, the likes of Wyoming and Montana are in with a shout. I don't think the quad bike helps either or the 1960s petrol pump - many Americans curiously own both quad bikes and petrol pumps.

The giveaway surely is the museum collection of chainsaws. I confess to never owning one and would be troubled if any of my mates kept one in the cupboard. To own four and then place them in a line as if they were trophies would be a deeply disturbing sight anywhere in the US other than Alaska. To most of the world’s population, chainsaws have a sinister symbolism, but to Alaskans they are mere cutlery. I also suspect that in the woods of Alaska a few locals will shave with a chainsaw. Where we are staying in Katmai, I swear there is a better chance of finding a chainsaw in the local grocery store than a lettuce.

When I was a kid, a favourite item to add to your list for Father Christmas was a tool kit. I never got one and now in this technology age, Father Christmas is asked for fewer and fewer tool kits - and parents would actually find it odd if it crept on to their son’s list. “Darling, we need to talk about Kevin”.

But in Alaska, kindergarten kids will arrive at school with their tool kit as if it’s their pencil case. To get to your 6th birthday and not own a hammer risks being chased by a screwdriver wielding seven year old when the teacher will be too busy sawing up her desk to give a damn. People are made differently out here - when Russia sold Alaska to America for $7m in 1867 everyone won. The Americans won, as it increased their access to natural resource and Russia won as there was more alcohol to go around in Moscow.

When we go to Alaska, we stay with a man called John. He is a legend - so much so that he has a street named after him - you can see the street sign on the side of his shed. John has more trucks than anyone else I know and they are all parked just off John Street. The principal room in his lodge is one of my kids’ favourite rooms. It is basically a bar with a big television, a stuffed 1000lb grizzly bear, 27 guns and a polar bear skin behind a dart board. In the evening men from all walks of life that involve fishing congregate at the bar and play dice games and drink. They do exactly the same in the morning too. The irony is that the village is a dry town - a development initiated to reduce alcohol consumption. Red rag to a bull.

If I was ever to spend a night in the tundra without John, I would feel an unease, but with him there is a sense of safety. The thing is that he has seen it all - plane crashes, bear attacks, drownings and monster fish. He is the Crocodile Dundee of Alaska and we are so lucky to know him. If Hemingway had met him, John would be famous. His character should be immortalised by pen.

The traditional story of human migration in the Americas goes like this: A group of stone-age people moved from the area of modern-day Siberia to Alaska when receding ocean waters created a land bridge between the two Continents across the Bering Strait. It is doubtful we will ever know the truth in this, but what is for sure is that the sights available on a Saturday night in John’s cabin would give stone age life a run for its money in visual content.

"We can either go with the crowd or avoid the crowd and there can be no doubt where my mindset is"

When we were up there this year, we had the pleasure of the company of a Japanese party of six. They were clearly men of both financial muscle and sophistication, but every year for 12 years they have eschewed the rich culture of contiguous America and Four Seasons Hotels to spend a week camping in the wild Alaskan tundra. They return exhausted and wet to recover in John’s cabins - an interesting choice given what they have just put themselves through. But they love it, just as we all do. It seems a sure bet that every year from now on in the last week of July, whisky, dice games, corn beef hash and cornhole will unite a random group of Americans, Japanese and Scots. This is the wonderful world in which we live.

Many of the animals that I photograph are under pressure in today’s world of poaching, hunting and - most threateningly of all - population growth and habitat loss. Those that focus on poaching as the key threat are moved by the same emotional and spiritual pulls, but at some stage there will be a tipping point in the conservation movement when human encroachment is accorded the highest risk weighting. The problem is that “encroachment”, unlike hunting and poaching, is not a headline grabber.

Encroachment is - in the main - not an issue in Alaska and the bear population of 30,000 is not under pressure. But there's a big old fight looming. Pebble Mine’s plans to operate in Bristol Bay - the epicentre of the 50 million strong annual sockeye salmon run - will be the mother of all test cases in this age of enlightenment. Bristol Bay is unfortunately the home of one of the world’s biggest unexplored copper and gold deposits - that is the thing about rivers - they have created other bedfellows for the fish.

The fishing lobby is strong in Alaska and the EPA has received over 1 million public comments arguing against the Bristol Bay development. But the mining lobby is not weak either and then we must remember the mindset of the current Washington administration.

I would forecast that Bristol Bay will soon be a name that is familiar to more people than fishermen. This village at the end of the world now has a material global relevance as we rapidly adapt our conscience to declining planet biodiversity as a result of human behaviour.

Bears are easy to photograph in Alaska, they are just not easy to photograph well. There are many places I have learned not to go because of human footprint, regulation and rules. We can either go with the crowd or avoid the crowd and there can be no doubt where my mindset is. Original content is a buzz expression because the two words need each other and never more so than in 2018.

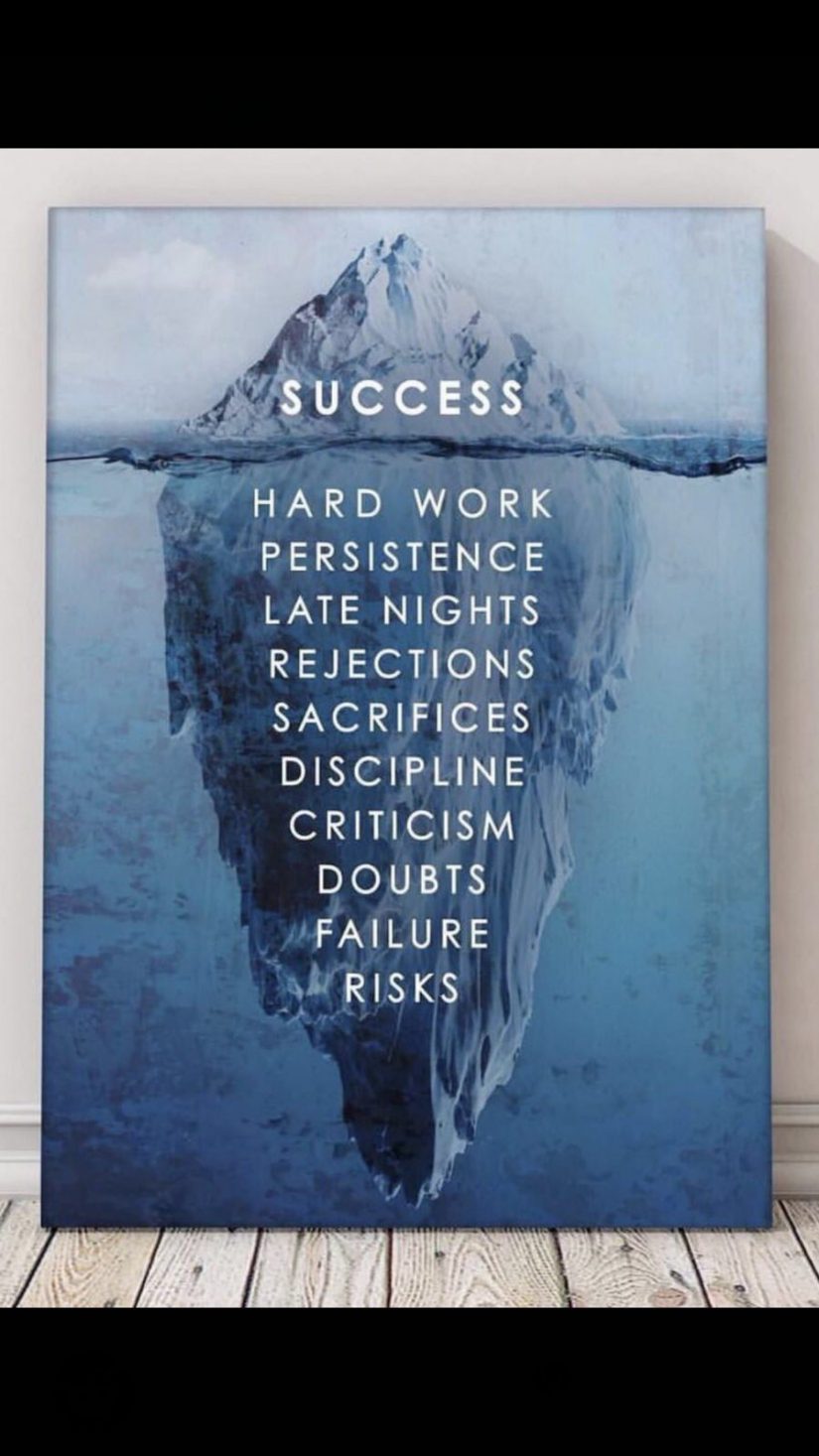

It should not be easy to garner strong original content and through all our failures we do remind ourselves of this. We probably all know the Iceberg metaphor here and I think the poster should hang on more walls in colleges and startups than it does, because it prompts and reminds. Of all the destinations that I work, its message holds most true for me in the tundra of Alaska.

Risks

Looking at the bottom of the iceberg, we do take risks up in Alaska - not really with brown bears, because although the big guys and sows are very big and although there is an average of 14 attacks in Alaska a year, we know our game here and we also turn up when they are fishing. A bear fishing is a bit like grown adults watching their country play in the World Cup - nothing else for that period of time matters. Bears tolerate human presence 99.99% of the time in Katmai in July and August and those that suggest otherwise probably have a mission to big up their implicit bravery.

The risk is simply one of time. It usually takes four planes to get to my preferred location from any city other than Seattle or Chicago and I don't live in either of these cities. That’s eight flights on a round trip.

Failure

I have failed to bring home original content many times in Alaska and never more so than on my first visit in July of this year. The salmon were late, and so therefore were the bears. The rain was also so unrelenting that two of my cameras gave up on me. We persevered out of work ethic, but I knew that there would be little in the can to take home. On my final foray out in the wet, I fell down a path on a steep incline and when I landed my cameras had got to the ground before my back. A Nikon doesn’t do much to cushion a fall and that was that for my back and my photography for a while.

Doubts

Inevitably with failure, comes doubts about my camera approach with bears and indeed my location choice. In particular, I recognise that using a remote control unit high in the tundra to get the lens very close to bears is a low percentage shot. I have missed cigar images by two inches in my focus simply because I am 50 yards from the camera and the bear might not move exactly how I predicted.

There is always a much better chance of an image with a camera in hand as I can react to circumstances and movement. But then again that is what almost everyone else does. Of all the animals in the world that I photograph, bears are the ones I least like to photograph with telephoto lenses as it lacks creative courage. A bear’s movement along a river bank can be predictable in July and August and that affords the chance of working with wide angles and remotes. There is so much textural detail from four feet and so little from 50 feet. But then again, if you fail, doubt creeps in.

Criticism

To come home from Alaska with nothing, leads to criticism, mostly from myself. To lose cameras to conditions also could be seen as careless and to come within two feet of bears could be seen as being irresponsible. Criticism is part of the game.

Discipline

When there is passion there will be commitment but there can be issues with being disciplined. Excitement can lead to mistakes - low battery levels, too many lenses and too many choices. In Alaska, all we can do it make sure we are up early and then keep it very simple. There must be fresh energy and a thorough understanding of every mistake we had made the previous day. To make mistakes is natural, to make the same mistake on consecutive days is junior.

Sacrifices

To travel to a point in Alaska where Russia is only 90 minutes away by plane does mean sacrifices. To lose equipment is a sacrifice and to be out of touch with the office and home is a sacrifice. But all are more than manageable.

Rejections

I was rejected by art dealers for many years. Today new work can often fail to garner the interest that I would have hoped. This is true of my Alaskan series and everything else. Rejection is an integral part of a journey - it should simply provoke an intense determination to get better.

Late Nights

It’s not so much the late nights in Alaska, it’s that the nights start early in John’s lodge - like five pm. John’s bar demands both attendance and consumption. After a day walking many miles in the tundra - we are willing participants. It kind of goes with the territory.

Persistence

This is an easy behavioural trait. We will never quit and always be constant in our application. In Alaska, I think we have left pictures up in the mountains and will always believe that. We will keep going back. I went back again last week when my back had sorted itself out - I had no choice.

Hard Work

There are many easier places to photograph bears than Funnel Creek. Wading down the river with a ruck sack of cameras mile after mile is not the easiest of days, especially when 1000lb bears could be around every bend. Throw in the rain and wind and it can be a tough day at the office. The alternatives such as Brooks Falls are, however, far too mainstream and comfortable. We asked for the wild and this is the wild.

Success

The tip of the iceberg is not something we dwell on. Over time we will have our moments and the picture - Ted - makes it all worthwhile. We will be back for more.