Letter From Kigali

Hugh McIlvanney - unquestionably one of my all-time heroes - sadly passed away in January. He had been poorly for some time, but the out-pouring of grief in Fleet Street gave an insight into the deference and love that his fellow professionals had for him. He was the greatest sports journalist of his generation and probably a few generations either side.

Like his fellow Ayrshire man, Robbie Burns, Hugh was a genius with the pen and I hung on his every word when he was at the Observer and then at The Sunday Times. No matter the sporting legend - Ali, Stein, Busby or Ferguson - Hugh had access to their souls, as he was the “Don”.

On GEORGE FOREMAN VS MUHAMMAD ALI, ZAIRE,

1974, (the Rumble in the Jungle) McIlvanney wrote:

"We should have known that Muhammad Ali would not settle for any ordinary old resurrection. His had to have an additional flourish. So, having rolled away the rock, he hit George Foreman on the head with it.”

On SIR ALF RAMSEY:

“How many caps have you got?” the venerated England manager Sir Alf Ramsey asked him, after he had criticised the team’s performance. “None,” McIlvanney replied, adding, “but if I send a turnip around the world, it doesn’t return an expert on geography.”

A paragraph in The Guardian’s obituary nailed it:

“His searing intelligence and an old-fashioned regard for accuracy, embroidered by a gift for verbal musicality, lifted his work to sometimes operatic heights. Others might have been more concise; none was more precise. He cared with monk-like zeal about the layered subtext of his narrative, as well as hitting the right tone and rhythm in his prose, and packaged it all as Beethoven might put together a symphony”.

In 1986, I found myself as a young and average 20-year-old photographer somewhat friendless and lonely in Mexico City during the World Cup. In a sprawling city of 10 million people, I knew precisely no one. But I was resourceful enough to know which Five-star hotel Hugh was staying at, so I rather cheekily left him a note at reception to see if he fancied a drink on the forthcoming rest day. This was before mobile phones - so it was not easy for him to find me and besides, he had absolutely no idea who I was, there was no website to refer to and no editor to speak to, as I had winged it with a press accreditation from a football magazine with an annual revenue of less than £50,000 per annum. Mexico was "the last days of disco" in press accreditation.

Hugh was the rock star of the whole British press contingent and I was just a kid who had blagged his way in - it was a boxing mismatch and to Hugh, boxing was a metaphor for life. And so it was, with some shock, that I received a message at the press centre from Hugh inviting me to the cocktail bar at the Camino Real in Mexico City for a drink.

There was never just one drink with Hugh and I remember staggering home later that night to my modest hotel across Zocalo Square. I was inspired and energised from listening and drinking with a national treasure. He was a colossus - precise, passionate and unique.

McIlvanney’s relationship with Ali and his prose allowed his coverage of “The Rumble in The Jungle” in Kinshasa in 1974 to transcend the work of others and it was probably the defining point of his career.

When I myself headed to the African Equator last month - albeit to Rwanda as opposed to the DRC, Hugh was very much in my mind. I had always struggled to deliver in this part of the world and I needed - if nothing else - to employ some of “the monk like zeal” recognised by The Guardian. If I could be, I should also be precise, passionate and unique.

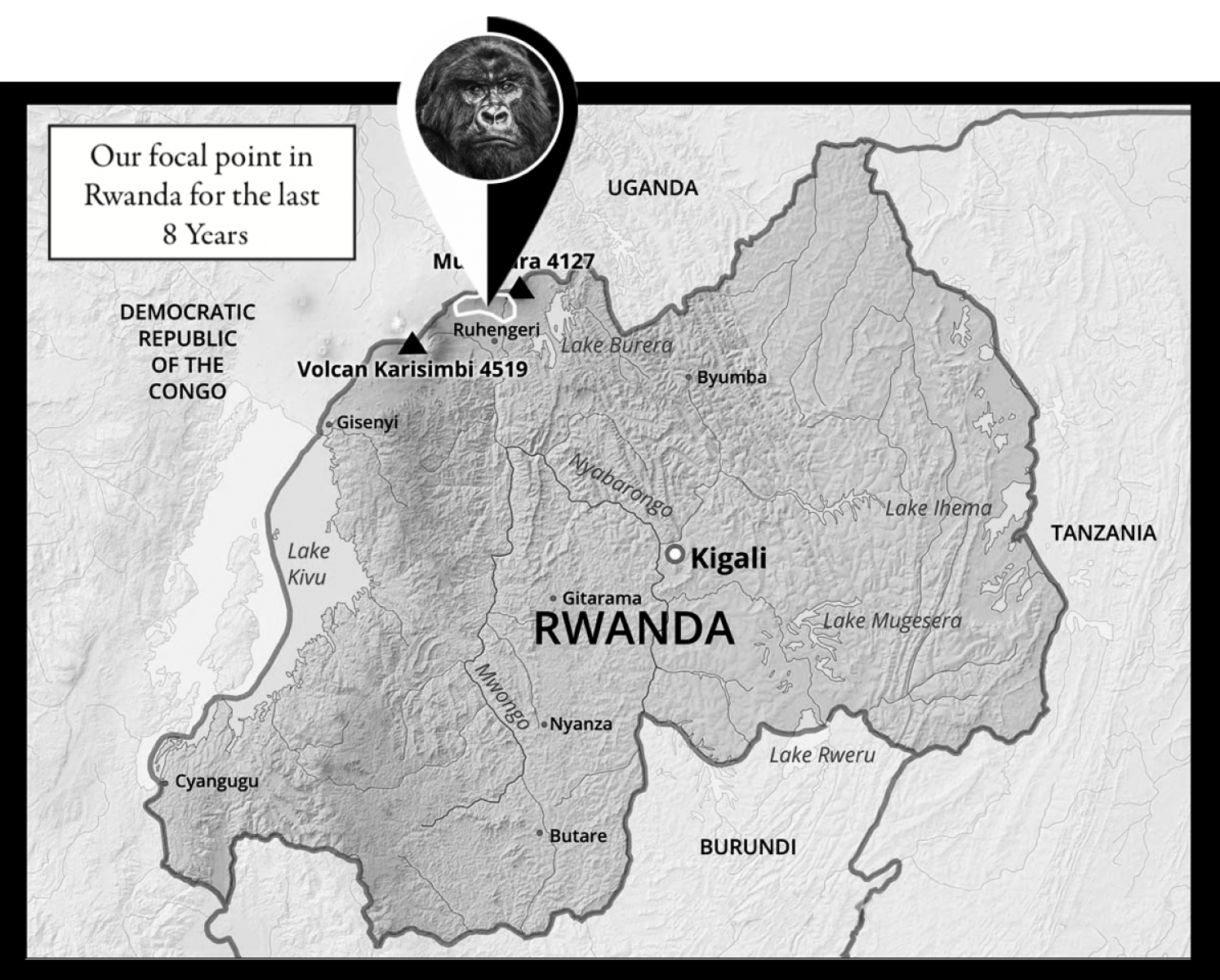

I have now been to Rwanda seven times - that’s a slight insight into my life, after all Reading is only an hour from London and I have only deliberately been there once (the train station does not count).

A couple of weeks have passed since I returned from my most recent visit to the country and it has given me time to distil and be slightly more emotionally withdrawn from an assignment that has challenged me throughout my career.

There is a delicious irony in that some think the challenge for filmmakers in Rwanda is that it is deepest Africa at its corrupt worst - a land of untamed geology, menacing mountain gorillas and a tribal hatred. The truth is the reverse, in that Rwanda is now so tame and safe that it has become mainstream. There is more chance of finding fast broadband in the mountains than a machete. And so it is that the challenge is now to make Rwanda look raw and untamed, not to overcome the perceived raw and untamed.

Last month, when I spent a bit of down time in Kigali, the country’s burgeoning and educated capital of 1.2 m people, I wondered whether Kigali could well be the safest large city in Africa in 2019. Granted, Windhoek - the multi cultured capital of another former German colony, Namibia - is not a place mentioned in dispatches with trepidation, but Kigali is five times the size of Windhoek and located in the heart of the continent’s mountainous equatorial heartland, not in some isolated desert at the West foot of white sub-Saharan Africa.

I have been to many dangerous cities in Africa - Nouakchott, Nairobi, Lagos, Dar es Salaam, Johannesburg, Harare and Juba to name a few and Kigali represents the continent’s antithesis to these troubled places. Indeed, crime rates in Rwanda are running at 10% ofthose in South Africa. London is now unquestionably a more dangerous city than Kigali - not a statistic that would have received many bets in 1994. Rwanda is, on many levels, Africa’s poster child.

There are some filmmakers and still photographers who, out of self- interest, choose not to dampen the misconception that Rwanda is a dark and unruly place where angels fear to tread. The country’s name evokes imagery a world removed from neighbouring Kenya and this is a direct legacy of the genocide of 1994 that claimed 900,000 lives. Ostensibly, travelling to Rwanda should have mystique and a sense of foreboding, but those days have gone and therein lies the problem for filmmakers. The gorillas have been photographed to death.

Every day in Volcanoes National Park in the North of the country, at least 60 people are taken up the hill to the rainforest by the guides. This now costs $1500 per person, so on my maths, Volcanoes National Park generates $30m a year alone just from gorilla trekking. Then throw in new six star hotels that are sprouting up on the edge of the park - Singita and One&Only both open next year - and there is something quite seminal going on here. This is no longer just the home of “Gorillas in the Mist”, it is the home of “dollars in the mist”.

In some parts of east Africa, it can often be too casual to suggest that this degree of investment necessarily trickles down to every level of the community, but in Rwanda there is palpable evidence that it does and I have the trips on my side to give context to the rate of progress.

Conservation NGOs talk much of the importance of an holistic approach to their efforts and the importance of including the local communities in their awareness and investment initiatives. It sounds good on paper and often I find myself rather disillusioned with all the powerpoint sound bites that never really appear to be implemented.

In Rwanda it does happen and I would go as far as to say that the country is now the paragon in holistic conservation efforts. President Paul Kagame may have his critics - all Presidents do - but endangered species have had no better political leader in Africa. I think Clinton, Bush and Obama would all endorse that last sentence.

The mountain gorilla population rises every year and, in the valleys below, there is job creation, overseas investment and improving roads and education. Crime is minimal and yet only 25 years ago, over 5,000 people were killed daily for three months in the radius of 100 km south of the park and many more were raped. To mention Tutsi or Hutu is now seen as ignorant and disrespectful. It is difficult to believe that there is a greater story of human redemption on the planet.

The problem for filmmakers in Volcanoes National Park starts with the acknowledgement that access and sightings of gorillas are guaranteed for everyone. There is no special pass or VIP seats - even for the BBC. Furthermore, only one hour with the troop is permitted and this - depending on the length of the trek - tends

to be anywhere between 9.30 am and 11.30 am. In most other parts of equatorial Africa, I will have finished filming for the morning by then - as the sun is too high. The sun is often diffracted and blocked by the canopy of the jungle - resulting in high contrast, unfriendly dappled patterns on the floor.

The even bigger issue is that gorillas tend to be found in very dense parts of the forest where there is no sense of place. This reduces the ability of the cameraman to make his mark. The most evocative of images I have seen from this national park tend not to be portraits, but rather photographs with a more layered narrative. Contextual composition cannot be delivered if it is not there in the first place. This has always been my hurdle. More often than not, I know within an hour of arriving at a location with gorillas, that I am doomed to failure.

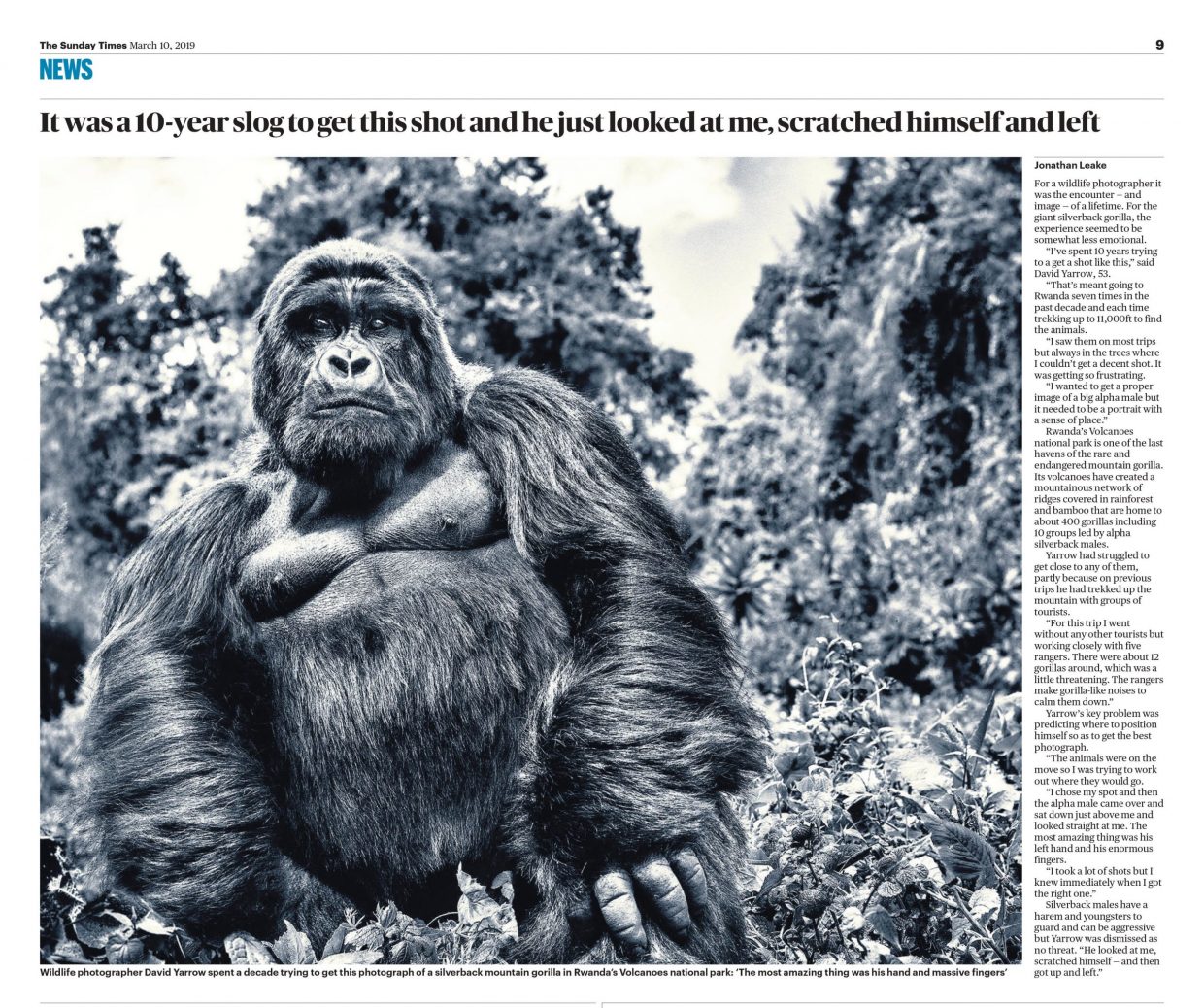

The most impressive feature of the lead Silverback is his immense size and this does not tend to be conveyed well from the majority of camera angles. I have long worked on the premise that with every animal I am photographing, the starting objective is to do justice to the magnificence of the animal. With silverbacks that dictates a responsibility to capture a sense of scale. This requires context and almost always, the camera needs to be below the whole gorilla.

In a rainforest, the cameraman almost always has to be reactive, not proactive and when there are several people in the group, the ability to take control is even more marginal. Ostensibly the difference between a good opportunity and a less good one, may well look marginal to the outsider, but for seasoned filmmakers it can be night and day.

Big original content moments in the wild often emerge without warning and involve more luck than application. However, I would strongly contend that the photograph “Judge and Jury” - which is featured in several places in this newsletter - was firmly earned.

By getting it wrong for many different reasons, I finally solved the jigsaw puzzle of how to get it right. The starting point was never to quit - that is unacceptable. But on this occasion, I had the right lens, the right camera body, the best rangers and most importantly I was on my own. The silverback - who I have met before - was not distracted as he only had me to focus on. I do believe that is conveyed in the image. My position - two feet below him on a hill with a backdrop - was the craved-for position.

I am not sure when the Sunday Times in London last allocated half a page to a photograph of a wild animal, but when they did last week, I do believe that they made a good decision. It made all those treks up the mountain since 2008 more than worthwhile.