Letter From Maun, Botswana

On Monday August 19th, I had a lively lunch with my São Paulo gallery partners ahead of our exhibition that evening in the city. We left the effortlessly hip restaurant at around 3 pm to head back to the hotel to change, but when we stepped outside, the street was almost in darkness. We knew it was winter and the forecast was for heavy rain, but this seemed an almost biblical rainstorm in the making.

My Brazilian friends, knowing Scottish weather, joked that they’d organised it to make me feel at home. As we walked to hail a cab, it just got darker and darker and I remember saying to my companion that it seemed like the start of the movie “Independence Day”. It was eerie and almost apocalyptic, but I thought no more of it and the thunderstorm duly came as we were being driven back to the hotel.

The next day we were all aware of what had happened as São Paulo and Brazil were at the centre of world news. The largest city in the western hemisphere had had a blackout because of the smoke from the Amazon bush fires. I don’t think I will ever forget that day - it was when it was rammed home to me that the world, as we know it, is indeed teetering.

My cameras were all in Johannesburg, so the idea of being spontaneous and flying into the Amazon was logistically too challenging and so, with some regret, I flew back to Botswana where we have spent a good deal of August. To leave Brazil may have been the wrong decision, but I will never know.

Botswana is the size of Texas, but boasts a population only a quarter of that of the Dallas Fort Worth area. However - like Texas - precious natural resources below the ground have given the region great financial muscle. The country is the second largest producer of diamonds in the world and this has propped up the percentage per capita economic growth which at times has only been bettered by China. The Government of Botswana remains one of only two shareholders of De Beers - the other being the mining giant Anglo American. This is not a normal African country - the Government is cash rich and the country works. The majority of African countries do not work.

As a result of this, and the depth and range of the wildlife, Botswana is extremely popular with big wallet tourists and it has become the Disneyland and Four Seasons of African safari destinations. This can be a problem when garnering original content, as it is all a little mainstream.

It is Disneyland in that up in Chobe, by the border of not just Namibia, but also Zambia and Zimbabwe, double decker boats take 70,000 tourists a year to see elephants swimming across a river. These visitors, with popcorn in one hand and mighty telephoto lenses raised on a gimbal in the other, wait for elephants to swim across from Botswana to Namibia or Namibia to Botswana. This is no Dover to Calais David Walliams crossing - it’s just 100 yards in places. The crowds also make it my idea of hell.

I have never seen more photographers in a working day than I did on my visit to Chobe and that includes covering the Olympics. Chobe can make the Masai Mara look empty. From the gallows of my own boat, I was crying to be shipped to North Korea - at least there I could work on my own. The operators of these day trips spin a yarn about a magical adventure of serenity in the heart of Africa, whereas in reality, it is about as serene as Heathrow on a bank holiday weekend. I don’t fully understand why a raised gimbal helps the photographer either - but that is for them to worry about not me.

As an aside, I am not sure what it is with the human fascination with animals swimming, but it is certainly a feature of our generation. Dogs in ponds, wildebeest and zebra in the Mara and horses almost anywhere. Animals swim - let’s get over it. If this obsession was reciprocated and animals could attend next Summer’s Olympic Games in Tokyo, the black-market tickets for the swimming pool would be nuts. “Screw the athletics, we want to see humans swim”, cried the giraffe from the IOC.

Botswana is also manifestly the Four Seasons of African Safari destinations. Smart people that know the value of money can pay $2500 a night to stay at the famous lodges such as Baines in the Okavango Delta. On my maths, that is one third of the GDP per capita of the country. The mattresses and the breakfasts better be damn good at those rates.

I can imagine couples on their first night at Baines, having a good bout of misplaced romanticism.

“Everyone, this is Hal and Nancy from Florida - it’s their first time in Africa and they are having an absolute ball”.

“Oh yes we are, Stacey, we love Africa and all them darn cute animals in that marsh. It is all so wonderful and I don’t see any crime anywhere”.

Sadly, as we know, the luxury camps of the Okavango Delta are not representative of root and branch Africa - that honour goes to Nairobi, Jo'burg, Dakar and Lagos on a Friday night. When you fly over the Delta at a low height, it resembles the most exclusive of private members' golf course in Connecticut - all water hazards, big bunkers and then verdant greens. No golf is being played, but it does have luxury brand written all over it. It is easy to perhaps romanticize over Africa when staying in the Okavango. It is this corrupt and vast continent putting on its “Sunday best”.

But I am all for a bit of comfort from time to time and it would be disingenuous of me to suggest that the problem with Botswana is that it is a little spoiling. It is also busy, but not everywhere is as congested as Chobe. There are vast areas of wilderness, as suggested by the low population density.

My primary issue with filming in Botswana is that the elephant - the greatest of all African animals - is a shadow here of his Kenyan cousin. I like to work with big elephants and nowhere competes with the bulls of Amboseli and Tsavo. I see little point in photographing individual elephants in Botswana - diamonds yes, but elephants no.

However, when I worked on a high-profile fashion shoot for Harper’s Bazaar in early August in Savute and the Makgadikgadi Salt Pan, it struck me that there was an opportunity to turn the cards that Botswana has been dealt to my advantage. There is an abundance of wildlife in the reserves and in the dry months there are often large congregations around watering holes as the day gets old. At the end of the dry season, the availability and location of water dominates animal behaviour. The elephants may not be mammoths in Botswana, but this is the highest density of elephants in the world.

Maybe we could take a picture that illustrated the density rather than size of Botswana wildlife. 130,000 elephants roam in the country - more than a third of what’s left in Africa. That is surely a statistic to be played with and worked into a concept.

Over the years, I have visited many human watering holes in the UK and the US and also many animal watering holes in Africa. I have my favourite pubs for sure, but until this summer, I had yet to find a practical watering hole to work with in Africa. The problem is that many of these animal destinations are either heavily regulated or located on land that is flat thus removing the chance to really convey depth. There are a load of vanilla waterholes in Sub Saharan Africa that offer nothing for the artist. We try to avoid doing anything that is banal and most of these water sources are just that.

What I needed was not only a watering hole in which I could be out of my jeep and on the ground, but also one with a hill behind it that would offer the chance of a layered composition. In Etosha, Namibia I certainly could not find it and in the acclaimed reserves of Botswana I struggled as well. I saw nothing that excited me as a potential canvas. I wanted to frame a scene that played on numbers, but this would not happen if many of the animals were hidden because the land was flat. Location scouting in the heat of the day can be soul dispiriting and exhausting work and there have been a few days this summer in Botswana when I haven’t even taken my cameras out of their bag.

Then, late one day in the wilderness of Savute, I found my spot. It was not only on private land rather than a reserve, but there was a hill that framed the entire western side of the 200 meter long water source. This offered the chance to bring my vision to reality as it could be a canvas for a layered narrative. The next day we set up and just waited and waited, but not one animal of note turned up and we had no more days to spare as I was then committed to a project elsewhere. We could not believe our bad luck - locals told us that this had not happened for weeks.

Savute is not the most practical place to leave and return three weeks later, but I knew immediately that that was exactly what I was going to have to do. After all, I had found my spot, it was just the actors that were missing. When I have an idea, and believe in the concept, I can’t leave the project in the bottom drawer gathering dust, I need to follow through and get the job done when the energy is high.

Amongst other things, visiting Savute involves transiting through the crazy airport of Maun - near the Okavango Delta. The final frontier “Mad Max” town of Maun is a dispersed and dusty outpost of only 60,000 people, but bizarrely it boasts one of the top three busiest daytime runways in Africa - because of the charter activity and the fact that the airport is closed at night.

This is quite an insight into the popularity of Botswana as a tourist destination - a town of 60,000 people serviced by a busier airport than Cape Town or Lagos. The other clue is the size of the ex-pat community in Maun - it really is a bizarre place - a bit like Queenstown in New Zealand, there is a palpable sense of travellers passing through an extreme outpost. Strangers unite in their sense of cutting edge adventure and yet the most expensive accommodation in the world is around the corner. Maun is something of a paradox.

I worry incessantly about crowded destinations as they tend to be the enemy of authenticity and original content, but I somehow doubted anyone was arriving at safari “ground zero” with the same plan as me. I was not there for the cats, I was there for the numbers. Cats and numbers are mutually exclusive.

As it turned out, it was a trip worth making and I had my moment at around 10.55 am at the watering hole. It’s cold at dawn in Botswana in August and watering holes only get busy when the sun warms the air. It will always be sunny - in 12 days in the country in August I did not see a single cloud. There is more chance of finding a kangaroo here in August than a cloud. The higher the sun, the tougher the job for photographers and from 1 pm until about 4 pm, it is very tough. In retrospect, I think we got lucky to have this volume of traffic before 11 am. But we had worked for this image (Before Man) and I think we deserved our moment.

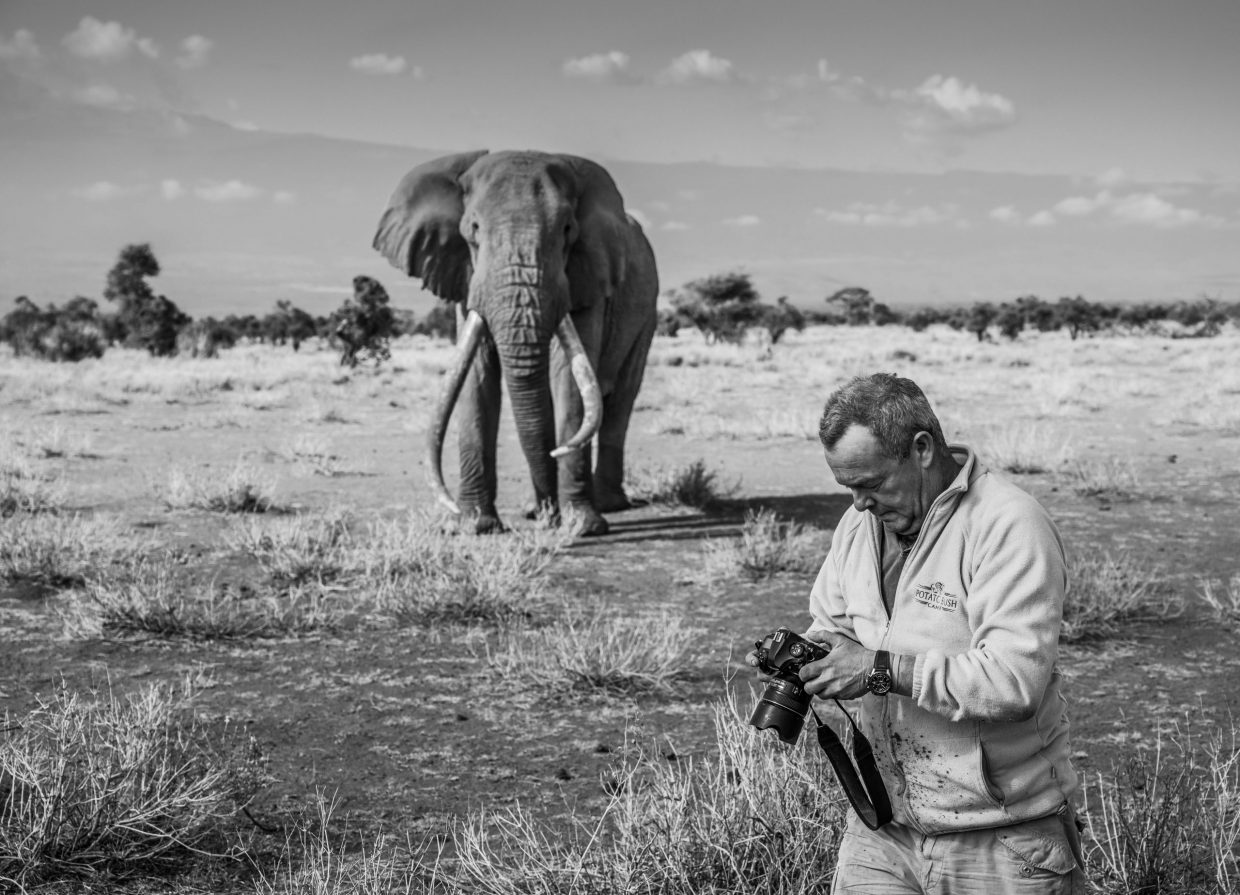

From Botswana, I joined a film crew in my favourite place to work in Africa - Amboseli, Kenya. It was my 21st visit in the last eight years. I feel I am playing at home in this elemental and dusty ecosystem - there is such familiarity and I do have the support of a great and well-established team. I often talk about DYP being much more of a team than is recognised and nowhere is that better illustrated than in Amboseli.

The bull elephant big tuskers here are rock stars and I still feel a visceral rush whenever I see Tim or Craig. For a year we have waited to go back as the dry lake - after all the rain of 2018 - had become a lake again. It is now finally back to being dry and hence we returned this August. Amboseli is a place that always gives and there is a responsibility to be at the top of our game. I wake early in Amboseli as there is something of a rush for me - we are in the land of giants and we have the team in place to find them.

It was again a successful week and much of the credit must go to my guide and friend Juma Wanyama. When his team found not just Tim, but Craig and several bulls together, at around 7.45 am one morning, he used all his skill to work the situation in my favour. It is one thing to find a big tusker (and he employs as good a network of Masai motorbikers on the ground as possible) but it is another thing to know - as a photographer - quite what to do when we find them. Juma and I have an invaluable understanding and it was clear to the team around us that week, just how much mutual trust there is. Not many can lie on the ground 10 metres from two of the biggest elephants in the world and feel safe. With Juma, I can do that.

The photograph from that morning - Squad - is a highlight of 2019 and may be even a little more. I am so excited to see it in print. We will have plenty of opportunities to show it, as our global book tour starts in earnest in September with exhibitions in Monaco and Oslo. A further 23 cities and resorts lie around the corner. Busy and exciting times.